Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

I started this site to be a source of factual information related to the history of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. Unfortunately, history can sometimes have darker moments.

It is important that we do not shy away from history, even if it is unflattering. All historical figures, no matter how beloved, said or did things that would be antithetical to the images we have of them. This is true for everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Mahatma Gandhi. It is also true of the Gracies.

Discussing the less flattering moments in historical figures’ lives is not designed to disparage them or diminish their accomplishments. It is just to look at them from a fuller perspective as real people. People who simultaneously did good and bad during their lives.

As discussed in previous articles, the actions, behaviors or statements of historical Jiu-Jitsu figures may appear inappropriate to us now based upon our current culture, however they were actually accepted as normal at the time. An example of this would be the overt racism utilized to promote fights during the 1920’s and 1930’s (not just in Brazil, but also in the US and Europe as well). It was common for fighters to insult their opponent’s heritage, nationality or race in terms we would deem unacceptable today. It was not just the fighters either. Journalists, in describing fights, would often associate various racial or ethnic stereotypes to the fighters’ performances, personalities and tactics. While these behaviors are abhorrent, we need to understand that they were considered the status quo at that time.

However, some behaviors were deemed unacceptable from the start.

João Baldi and the Steel Box (January 14th, 1932)

If you watched the Gracies in Actions videos (and everyone should), you will remember Rorion Gracie describing his “Uncle Oswaldo” choking the gigantic “John Baldi” extremely early into their fight. This is all true. What is not described in the video is the ugly fallout that occurred after that match.

João Baldi, born in 1880, was an extremely heavy, professional challenge wrestler. For most of his career, he was listed at well over 220 pounds (at a height of only 5’7”) and was often associated with Greco Roman Wrestling (Luta Romana), but also competed in No Gi Submission Grappling (Luta Livre) matches. He was active in documented professional matches as early as 1909 and as others of his profession would do, he would travel the country, perform demonstrations and engage in matches for pay. He was often billed as the Brazilian or South American champion of wrestling.

By the time he faced Oswaldo Gracie in 1931, Baldi was a battle-worn 51 year old. He was still a formidable opponent, but he was past his prime and had gained a significant amount of fat. His weight had ballooned to 275 pounds (some accounts had him closer to 300 pounds, but this was likely hyperbole). Oswaldo, while not fighting often, had recently defeated an opponent from Bahia (Northeastern Brazil) in a Vale Tudo fight. The second oldest of the Gracie brothers weighed 141 pounds and his opponent weighed 190 pounds. While how competitive a challenger the Bahian man was is a question; but it is clear that Oswaldo won by choke. This victory for the 27 year old Oswaldo provided him the publicity and name recognition to challenge the more established Baldi.

The grappling only match took place on November 19, 1931 at the Theatro Republica in Rio de Janeiro. The referee was Gracie rival Mario Aleixo. Leading up to the match, Baldi had refused to wear a gi top, demanding that he be allowed to wear his standard wrestling attire consisting of only shoes and trunks. For some reason, just before the event, Baldi was convinced to wear a gi top even though he had no real experience with Jiu-Jitsu, Judo or gi training. The change in attire effectively converted the match into a Sport Jiu-Jitsu bout. Regardless of his tremendous weight and strength advantage, Baldi succumbed to a collar choke by Oswaldo early in the first round.

While this match helped promote the Gracies and their brand of Jiu-Jitsu as a self-defense art that would allow a smaller person to defeat a much larger aggressor, it also caused great embarrassment for Baldi. While he was past his fighting prime, in his own mind and in the eyes of the media, he should have easily beaten the much smaller opponent. Before and after the match, the press described the two fighters as the mastodon and the mosquito respectively.

It is unclear what led to an escalation in tensions between the Gracies and Baldi after the match.

Some accounts claim Baldi announced the fight was a “work” (a match with a pre-determined outcome, AKA a fixed fight). I have not found any direct evidence of Baldi making this claim yet, but if it is true, it is easy to understand why this revelation would not sit well with the Gracies. The brothers, at the time, were fighting (literally and figuratively) to establish themselves in the worlds of professional fighting and martial arts instruction. Whether the fight was legitimate and Baldi was now tarnishing the Gracies’ image and their ability to promote themselves via the victory or if the fight was indeed a work and Baldi just revealed a secret; the Gracies wanted revenge. It is impossible to tell if the fight was indeed fixed. As mentioned in previous articles, it was common for people to claim real fights were fixed to preserve fighters’ reputations, but it was also common for people to claim fixed fights were real for the same reason. As best as I can tell, it was a legitimate fight. Oswaldo did not fight often and his fights, while setup to maximize his advantage, do appear to have been legitimate. When fights were fixed, they were usually scripted to be more dramatic, last longer and be more eventful. Why would the Gracies demand Baldi wear a gi and why would Oswaldo finish the match so early if they were confident Baldi was going to lose on purpose?

The real reason for the hostility, according to Baldi himself, was an incident that occurred on January 13th, 1932 at the Club Carioca de Box (Rio Boxing Club). While Baldi and Carlos were at the gym, Baldi claimed he asked Carlos for his pay from the Oswaldo fight which he had still not received to that point, two months after the bout. Baldi claimed Carlos refused to pay him and stormed off.

Whether it was Baldi claiming the fight was fixed, Carlos not wanting to pay him, a combination of those things or something else entirely; the Gracies decided to attack.

On January 14th, 1932, a day after that supposed Boxing club incident and a day before Helio Gracie would make his ring debut against Antonio Portugal, the Gracie brothers ambushed João Baldi. Carlos, Oswaldo, George and Helio attacked Baldi outside the Café Sympathia (ironically, the Café of Sympathy) in Rio. The exact details are difficult to confirm, but it appears that upon leaving the café, Baldi was surrounded by the four brothers (Gastão junior was absent). Without a word, they began punching and kicking him. One of the Gracie brothers (Carlos by some accounts) was armed with a steel box and repeatedly bludgeoned Baldi with it. A Brazilian Army lieutenant named Newton Medeiros passed by the altercation, jumped off the bus he was on and arrested George on the spot. It appears that Helio and Carlos fled from the scene. Various reports claimed Oswaldo was arrested with George or fled with Carlos and Helio (it is difficult to confirm).

Baldi was not happy with the attack and rightfully so. He claimed the Gracies were attempting to get “cowardly revenge” upon him and that if Jiu-Jitsu was supposed to be so great, why did they not use it when they fought him? While there were arrests, police statements and local newspaper coverage of the heinous incident, it appears that no formal charges or punishment were handed out to the Gracies.

It appears that Baldi was able to recover from his injuries and continued to compete for at least one more year. He faced Tico Soledade, Roberto Rhumann (two times) and others. However, whether it was his age, his weight or the lingering effects of his assault by the Gracies, he does not appear to have ever won a match again. I could not find any information on Baldi after 1933, but he likely retired from competition around that time.

Manoel Rufino and the Steel Box (October 18th, 1932)

Manoel Rufino dos Santos was another Gracie rival. He was born in 1900 in Brazil but stowed away on a ship and relocated to New York at a young age. There, he took up shelter at a local YMCA and was exposed to Catch Wrestling. While in the US, he had a few dozen documented matches and then joined the US Navy which allowed him to gain further grappling experience in Europe. After completing his degree in physical education and spending six years abroad, he returned to Brazil and began teaching grappling at the Brazilian YMCA, the Tijuca Tennis club and other Rio based schools and sports centers. Rufino would go on to teach catch wrestling to his student, Euclydes “Tatu” Hatem, who would be credited with creating the Brazilian No-Gi fighting style of Luta Livre.

Rufino was in attendance at one of the Gracies’ first fight cards. The event was Jiu-Jitsu vs Capoeira and held at on July 3, 1931 at the Botafogo Football Club in Rio. George, Oswaldo and Helio all had matches, while Carlos performed a demonstration of Jiu-Jitsu. The ruleset for the fights was somewhat convoluted, but could be described as mixed rules Vale Tudo with 10 second KO rules and no striking on the ground (Note: At that time, there were no “unified rules” for fighting and rulesets would vary wildly between events). George won his fight via disqualification as his opponent, Eduardo José Sant'Anna, illegally struck him while on the ground. Helio and Oswaldo appear to have won as well, but details were never published. Rufino was not impressed with the Gracies’ performances and the brothers’ demands for restrictions to the rulesets. By some accounts, Rufino entered the ring after the final match and challenged the Gracies to fight. Other accounts state that he challenged them via a newspaper article a week later. Regardless, Rufino was quite vocal about his doubt of the Gracies’ fighting ability and their method of negotiating rulesets to favor themselves.

Carlos agreed to accept the challenge and after many rounds of negotiations regarding the ruleset, the fight with Rufino was set. The fight was scheduled for five 5 minute rounds with one minute rest between rounds. The match would occur under no striking, submission grappling rules. Carlos likely wore a gi and Rufino likely wore grappling trunks. The match occurred on August 22, 1931 at the Estadio de Fluminense in Rio.

Accounts in newspapers after the match were largely consistent. Rufino dominated the first two rounds. In the third round, both fighters either fell out of the ring or were in imminent danger of falling out of the ring. The referee called for a halt to the action and Rufino stopped. Carlos took advantage of his opponent’s disengagement and tried choking Rufino. The referee, noting the foul, halted the action again and Carlos left the ring in protest. The fight was delayed for around an hour with officials trying to get Carlos to return to the ring to restart the fight. By some accounts, Carlos never returned. Other accounts state Carlos did restart the fight after the hour break, but then left the ring again and did not return. Regardless, with Carlos refusing to re-enter the ring, Rufino was declared the winner.

Rufino would continue to taunt Carlos for nearly a year. He would speak to the media and claim Carlos was a coward, a clown and a fraud for fleeing the ring and refusing to continue the match with him. He would also criticize the restrictive rules Carlos demanded; asking why Carlos was afraid to face him under longer time limits?

In July of 1932, a year after their match occurred, Carlos and Rufino got into a face to face argument. The two happened to be at the same café at the same time, the Café Mouisco. Rufino appears to have sat on Carlos’ hat which was left on a chair and the two men began jawing at each other.

On October 18th of 1932, Rufino would continue to prod Carlos, publishing a letter of thirteen questions for Carlos in the newspaper, Diario de Noticias. The questions were not designed to flatter Carlos. Amongst them:

· Why a month after the match, did you request the officials have the fight ruled a no contest?

· Why didn’t you take my student’s challenge (Manoel Lima)?

· Why didn’t you take Catch Wrestler’s Roberto Ruhmann’s repeated challenges?

· Why did you want to have a rest period between rounds?

· Why did you insist on 5 minute rounds instead of 20 minute rounds?

· Why did you originally want only 3 minute rounds?

· Why did you not continue to fight? Were you afraid?

· Why do you challenge other fighters on behalf of your brothers instead of fighting yourself?

He ended the letter stating Carlos knew nothing about Luta Livre.

The letter incensed the Gracies. What occurred next was almost identical to the incident with Baldi nine months earlier.

The evening after the article was published, someone (presumably one of the Gracies) called the Tijuca Tennis Club to confirm when Rufino would be arriving that evening. Carlos, Helio, George and Oswaldo then waited in a car outside the sports club. When Rufino arrived, the Gracies ambushed him.

Like the Baldi encounter, the fight was several people versus one. Also, like the Baldi beating, the Gracies bludgeoned Rufino with a steel box (it was believed to be Helio this time who utilized the box). Accounts of the fight describe that Rufino was hit on the head by the steel box and fell to the ground. Once on the ground, Carlos, Helio and George (Oswaldo remained in the car) continued to punch, kick and hit Rufino with the box. Eventually, people exited the club to see what was going on and the Gracies fled in their car.

Rufino was hospitalized and the police opened an investigation. The brothers were charged with multiple crimes. The Gracies mounted a legal defense that appeared to contradict itself. They argued:

· The attack was in defense of their honor

· They did not perform the attack and there was no evidence that they did

· And if they did attack Rufino, they would not need three people to beat him up

The trial of the Gracies was scheduled to occur in 1933. Details of the court proceedings have not been found, but on May 24th, 1934, the newspapers announced the Gracies were convicted of crimes related to the Rufino attack. Carlos, George and Helio were to all be sentenced to 2 and a half years in prison. On May 28th, the Gracies reported to the authorities to begin their incarceration. On May 30th, as the fallout of the incident continued, Helio and Carlos were formally terminated from their roles as Jiu-Jitsu instructors for the Policia Especial.

The Gracies were able to leverage their growing cultural influence and celebrity and utilized a student to help resolve the situation. Former, private Gracie student and prominent feminist poet, Rosalina Coelho Lisboa launched a petition to pardon the Gracies. Lisboa as well as the Gracie brothers happened to be friends of the Brazilian President, Getulio Vargas. On June 6th, 1934, after spending ten days in jail, Carlos, George and Helio were granted a presidential pardon.

Similar to Baldi, there is not much information on Rufino after the incident. But his lineage lived on through the teachings of his student, Eucyldes “Tatu” Hatem and his founding of the Luta Livre system of martial arts.

Luta Livre fighters would continue to battle Gracie students for sixty more years until the heated rivalry was largely ended after the September 26, 1991 Jiu-Jitsu vs Luta Livre event and the victories of Wallid Ismail, Fabio Gurgel and Murilo Bustamante over their Luta Livre opponents.

Note: Robert Drysdale believes that "steel box" is actually a mistranslation and in fact refers to brass knuckles. It is something that I am continuing to look into.

Carlos, George and Helio Gracie

Article detailing the attack on João Baldi.

The “Gracie Version” of the history of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu still remains popular today. However, being popular or oft repeated is not the same as being accurate. As I have attempted to clarify through my articles on this site, the story is much more complex than we have heard.

That being said, people often ask me what are the key differences between Rorion Gracie’s presentation of BJJ history and the more complete picture.

My answer focuses on four key elements:

1. The elimination of other contributors to create a divine and exclusive mandate

While the Gracies did innovate, contribute, fight, win and spread the art, the Gracie Version of the inception of BJJ eliminates pretty much everyone other than Maeda, Carlos and Helio. As we see on this site:

· A Brazilian was teaching Jiu-Jitsu in Rio before Maeda even arrived in the country (Aleixo).

· Maeda was not the first Japanese fighter to come to Brazil (Miyako) and he was not the only Japanese Judoka to teach Brazilians during that time period (Satake and others).

· The Gracies actually learned Jiu-Jitsu from other Brazilians (Ferro and Pires) who preceded them and did not create their academy from the ground up, but actually took over an existing one.

We often hear about the Gracies having professional matches against other fighters in Brazil. However, we don’t normally stop to think that those fighters would need to come from rival academies and that those rival academies would require other instructor lineages (Geo Omori, Takeo Yano, Ono brothers and others). We have even seen Gracies, who did not behave the way Carlos and Helio wanted to, be similarly erased from the legend (George).

The Gracie Version streamlines that dialog. Maeda was the sole source of knowledge; he gave that information directly to Carlos and then Helio transformed it on his own. It is designed to give the mandate of sole ownership of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu very clearly to certain Gracies and eliminate the contributions of others.

2. The removal of negatives from the good guys and positives from the bad guys to establish simple heroes and villains

A good story needs simple protagonists and antagonists. The Gracies were selling a product and their contributions through the history of BJJ had to always appear in a positive light. The traditional martial arts culture overtly preached honor, nobility and humility and Rorion knew he would need to frame the heroes of his story much the way that Nitobe Inazo applied idealized European chivalry (taken from King Arthur and the Knights of the Roundtable) to the tales of the Samurai to garner worldwide interest and acceptance.

As we see with the steel box incidents of 1932, the Gracie brothers could, at times, behave more like the mafia than the Justice League. For some reason, ambushing someone, outnumbering him and beating him with a steel box, does not often come up when people talk about the Carlos Gracie’s twelve rules to live by.

Similarly, Rorion knew that Helio’s losses would eventually be exposed. He volunteered stories of Masahiko Kimura and Waldemar Santana’s victories over Helio. The fact that Santana was a former student of the Gracie Academy and defeated Helio had to be addressed. Rorion needed to stop the public from considering instructors other than Helio and his sons as viable providers of Jiu-Jitsu knowledge.

Rorion could have mentioned Santana’s subsequent losses to Carlson Gracie, Euclides Pereira, Ivan Gomes and Kimura, but that would present additional problems. It would show that there were people outside of Helio and his sons, even people outside of the Gracie family, that were qualified standard bearers for Jiu-Jitsu. It could also imply that as these fighters beat Waldemar and Waldemar beat Helio, that their Jiu-Jitsu was better than Helio’s Jiu-Jitsu.

A much simpler solution was to vilify Santana as I detail in another article. He was a traitor, betrayed and took advantage of Helio. He beat up an older, smaller and weaker man. While that is one perspective, it can also be said that Santana started from humble beginnings and through talent and dedication developed into a tremendous competitor, Vale Tudo superstar and successful instructor.

Stories need heroes and villains. The cleaner the hero and the dirtier the villain, the easier the message can be conveyed to and remembered by the customer.

3. Embellishment/Exaggeration to make the story more memorable and impactful

As I detail in my article on Waldemar Santana, every time I have heard the story, Waldemar’s reported size grew and grew. He was 6 feet and 200 pounds. He was 6’2” and 220 pounds. He was 6’4” and 260 pounds. In reality, Santana was 5’9” and weighed around 180 pounds. That would make him the same height as Helio, but outweighing him by a still significant 40 pounds. But an even bigger opponent makes for an even better story. A win becomes more profound, and a loss becomes easier to dismiss.

This is a common phenomenon within Jiu-Jitsu (and storytelling in general). The hero is small, weak, too old/too young and outmatched. The villain is a gigantic physical specimen in the prime of his life. It is a very relatable scenario and we as humans crave the secret knowledge to allow us to overcome the odds.

This framework was not just applied to Helio’s biography, but we see it across many traditional martial arts’ creation stories. It was also used by Charles Atlas and others in the fitness community to sell equipment, supplements and workout routines. It can even be applied to the Russo-Japanese War and what inspired worldwide interest in Jiu-Jitsu.

Antonio Portugal is another excellent example. He was the opponent for Helio’s first professional match. While it is true that Portugal was a professional boxer, his statistics and attributes continue to grow with time. He has been called in some retellings of the story undefeated and a national champion of Brazil.

None of these are correct. Portugal was a journeyman boxer, finishing his career with just 7 wins. He was never listed as a champion (before or after the match with Helio). At the time of the Helio fight, Portugal’s boxing record was 5W - 12L - 1D and he was listed as a lightweight. It wasn’t enough that Helio beat a boxer. It would sound much better if he had beaten the Mike Tyson of that era.

4. Omissions of fact to leverage the Gestalt principle of Closure

I would like to perform a little experiment. If you remember Gracies in Action, you will remember Rorion mentioning the match between Oswaldo Gracie and João Baldi. Rorion mentions that his uncle choked out his opponent while people were still arriving at the stadium.

Now, picture the fight in your head. Which choke did Oswaldo use? Rear Naked Choke? Guillotine? Was the fight you pictured Vale Tudo?

You would be wrong. While Rorion’s account is factually correct, it did not mention MMA, Vale Tudo or anything else. You likely assumed since the Gracies were BJJ people that occasionally fought Vale Tudo against other styles, that this was a Vale Tudo match.

It was not.

It was a submission grappling match. No striking. Baldi, was a wrestler, but long past his prime and did not want to compete in a gi. However, Carlos and Helio insisted that Baldi wear it as a condition for the match. This essentially converted the bout to a Sport Jiu-Jitsu match. It was already an impressive victory due to the significant size difference between Oswaldo and Baldi, but it is better marketing if people thought of it as a Vale Tudo fight.

Many stories within the Gracie Version are relayed in a manner similar to above to leverage this psychological principal of Closure. The storyteller’s words paint a partial image, and your brain makes assumptions on the rest to complete the picture. The person telling you the story did not lie. You merely formed a reference and reaction that were incorrect.

Conclusion

As I have mentioned previously, I am not trying to be anti-Gracie. Neither are many of my fellow BJJ historians. However, we are forced into a difficult situation. If we are to talk about BJJ history, we must cite facts. Doing so, sometimes puts us at odds with others who have been relaying stories (knowingly or unknowingly) that are not based in fact. It is not about disparaging anyone. It is not about favoring one faction over another.

It is about the pursuit of truth.

I am reminded of a powerful quotation from Robert Drysdale’s excellent book, “Opening the Closed Guard”.

It is from 9th degree Red Belt and Helio Gracie student, Armando Wriedt. While discussing BJJ history during his interview with Robert, he stated, “The truth can’t have affiliation”.

Amen to that.

So, what do I think of the Gracie Version of our history? I think it is one of the greatest pieces of marketing ever created. I don’t mean that sarcastically. I mean that truthfully. While some of the story was crafted intentionally by Carlos, Helio and Rorion, other aspects of it were altered and embellished by others through the elements of human nature itself.

Our desire to have great heroes and nefarious villains, to overcome great obstacles, to obtain secret knowledge and to be more powerful creates a snowball effect on the smaller story. It grows and grows and takes on a life of its own.

The great irony here is that while the Gracie Version can be viewed as one of the best infomercials ever produced; informercials are often associated with scam products. Here, the Gracies leveraged this approach to market one of the most effective and valuable products to ever be sold.

Could BJJ have grown without the infomercial? Would the UFC have happened? Would we be training in it today, if not for the story? Maybe not.

Maybe we needed the Gracie Version after all.

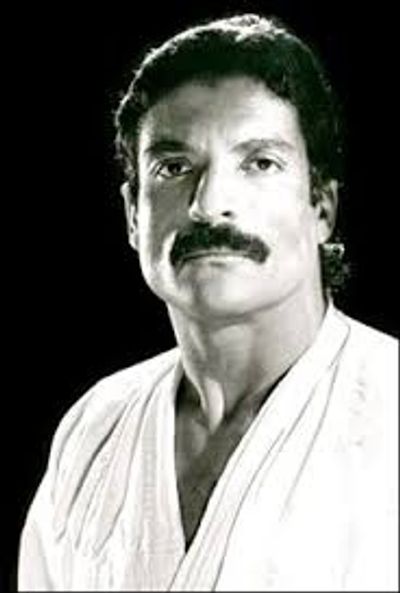

Rorion Gracie, the man most responsible for crafting the Gracie Version of BJJ history.