Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Note: I have constructed the below article based upon five hours of phone interviews with Craig Kukuk. I took the information he told me about his life and experiences and organized and edited the conversation into a more easily digestible and chronological format. Prior to publishing the article, Craig reviewed and approved the text to ensure I captured everything correctly. While I strive to bring a complete and accurate history of BJJ to the site, it is important to remember that the below is based upon Craig’s memory and perspective to the events (some of which happened decades ago).

Introduction

A big part of what I am trying to do with this site is to separate BJJ fact from BJJ fiction. I want to peel back the legends and myths and expose the true stories behind practitioners and events. I usually accomplish this by utilizing primary sources for the articles as opposed to word-of-mouth stories. This often involves leveraging contemporaneous newspaper articles and public records. Unfortunately, as much of my focus has been on the Foundational Era (1904 – 1942) and Television Era (1950 – 1979), many of the firsthand witnesses and participants are no longer with us.

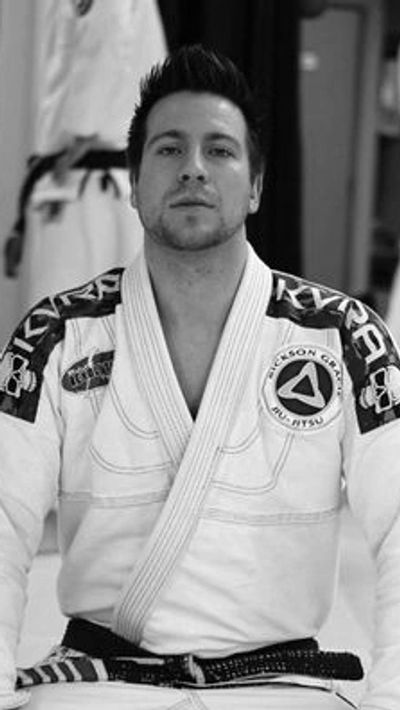

Craig Kukuk was my “White Whale”. The first American to be promoted to Black Belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu would be a tremendous source of information from someone who directly witnessed the birth of BJJ in America.

There was only one problem. Craig Kukuk, from as far as I could tell, left the community years ago. He stopped teaching, had no website and no social media. He didn’t teach seminars, write books nor do interviews. He really appeared to have just walked away from Jiu-Jitsu.

I was so intrigued by him and his story, but I also knew that if he had indeed left BJJ behind and had gone off the grid that there was little chance I could ever communicate with him. I had no idea how to contact him and I figured if I did, he would choose not to respond. I also knew that time was running out and I did not want to lose another valuable link in the chain of the evolution of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

I searched and searched for Craig and kept hitting dead ends. Eventually, I came across a business registration in Idaho with Craig’s name on it. I took a chance and did something pretty unheard of nowadays. I wrote him a letter. A real one. With paper and a stamp and everything. I sent it off to the business’ listed address and figured I would never hear anything, or it would be returned to me as an invalid address.

About a week later, I received a text from an unknown number, stating they would be happy to do an interview. It was signed, “Craig”. My first reaction was that I was pissed.

I thought it was a job scam or spam or some kind of con. I had put the mailed letter out of my mind and failed to put two and two together. I was getting ready to type back some very harsh words, when it struck me. It was Craig Kukuk!

Craig has always been an enigmatic figure to me. When I began training in 1995, he was already a Black Belt and had left the Gracie Academy. His story was surrounded in mystery. Every time I heard a tale about him it was told to me by someone with thirdhand information and it would often contradict other stories that I had heard. I wanted to get it straight from the horse’s mouth and now I had that chance.

Over the course of our several hours of discussions, I found Craig to be engaging, forthcoming, credible and still quite passionate about Jiu-Jitsu. I hope you enjoy.

Early Life

Craig Kukuk (pronounced Q-cuck) was born in 1961 in Torrance, California. He grew up playing football, boxing and wrestling. Craig graduated from high school in 1979 and began working in his father’s automotive glass shop to make ends meet.

Craig, with a background in combat sports and having a large frame at 225 pounds, was interested in continuing to train in street effective fighting techniques. He had recently started training in kickboxing, however, during this period, Karate was all the rage across the US, with many instructors making outlandish claims regarding their abilities.

While out running errands one day, Craig wandered into a Karate studio to see what it was all about. Craig asked the instructor if they sparred at the school. The instructor replied saying that they did not. Then, Craig asked the critical question, “Then, how do you know it works?”. Frustrated, Craig left the Karate school, but continued to maintain his desire to learn effective and proven techniques.

The Gracie Garage

In 1981, when Craig was 20 years old, a friend approached him with a training opportunity that he thought would give Craig what he had been searching for. The friend said a group of men had performed a demonstration of Jiu-Jitsu at his school, El Camino College. During the demo, the martial artists challenged people in attendance and did full contact fighting. Craig felt it was exactly what he wanted.

His friend gave Craig the address that the Jiu-Jitsu men had provided to the spectators and Craig hopped in his car to seek out their instruction. At first, he was confused as the neighborhood he was driving through, the Hollywood Riviera, was very residential and was not likely to have any kind of martial arts school within it. As Craig slowly drove down the streets, a man wearing a kimono came out of a house’s garage and ran towards Craig’s car. It was Rorion Gracie.

Craig had his first lesson that day in Rorion’s garage. There, Rorion introduced Craig to a small, quiet, fifteen-year-old Blue Belt sitting on the floor in the corner of the room. His name was Royce Gracie.

Rorion probed Craig’s background and intentions. As was common during this era, the Gracies would attempt to gauge whether an individual was looking to challenge and have a fight or was instead there to learn as a student. Once Rorion was satisfied with his investigation, he told Craig to do whatever he wanted to do to the much smaller Royce (striking was excluded). Craig shot in with a double leg, took Royce down and ended up in his guard. As Craig had a wrestling background and Royce was stuck with his back to the mat, Craig thought he had won. That was before the young Blue Belt spun into a straight armlock from guard and forced the much larger Craig to verbally tap.

Craig, never having any exposure to submissions, exclaimed, “What was that! That was cool! Do it again!”

Rorion explained that his family’s brand of Jiu-Jitsu was, “like wrestling with submission holds”.

Royce and Craig then had a second match. Craig shot in for another double leg, Royce sprawled, spun behind, took Craig’s back and finished him with a Rear Naked Choke. Craig was hooked and committed to start training in Gracie Jiu-Jitsu.

In those days of the Gracie Garage, all classes were taught as private lessons, one on one. So, while other students had started training prior to Craig, most notably, Richard Bresler, Craig did not have much opportunity initially to interact with the other first-generation students.

Craig continued to train at Rorion’s Garage until it closed in 1989. He took five private lessons a week with usually Rorion or Royce, but he would also be taught by, Royler, Rickson, and Rolker when they would pass through. In addition to the private lessons, Craig would spend additional time on the weekends rolling with his friends back at his house or at their homes.

Assuming Craig did 20 privates a month for eight years while at the Gracie Garage, he would have spent almost 2,000 hours on the mat learning from some of the most legendary Jiu-Jitsu men of all time. This would all be before there was ever a formal, US-based Gracie Academy.

Training at the time focused on Street Self-Defense/Combatives and they wore gi’s most of the year, changing to t-shirts and gi pants for the summer months. Craig felt and continues to feel that No-Gi was and is the more realistic and more effective training format but acquiesced to the uniform his instructors required. The only exception to the rule was Rickson, who appreciating the challenge given by Craig’s size and skillset, would almost exclusively focus on No-Gi when the two trained.

Craig’s belt promotions were typical of the era and were completely informal events, free of ritual or celebration. He was merely handed a new belt and went back to training. He received his Blue Belt from Rorion while training at the garage.

First Trip to Brazil

In 1983, Craig ventured to Brazil, staying with Royce at Helio’s apartment in Rio de Janeiro. Regardless of their five-year age difference, the two became close friends and would spend their days training at Gracie Humaitá (the Rio-based academy which was headquarters to the team of Helio Gracie and his sons). Craig did speak a little Portuguese at the time but found little need for it as many of the Brazilians at Gracie Humaitá, who were mostly from the upper class, were eager to practice their English with the visiting American.

While Craig had originally planned on staying there two months, he developed an abscess in his mouth. The infection required medical attention and Craig ended up leaving Brazil after 6 weeks to get it addressed in the US. It was either during this trip that Craig received his Purple Belt from Royler at Gracie Humaitá or he received it from Rorion immediately following his return to the US. Craig does not remember which.

The First US Gracie Academy

Rorion elevated Gracie Jiu-Jitsu to the next level by closing the Gracie Garage and opening his first, dedicated Jiu-Jitsu academy in Torrance, CA in 1989. It was there that Craig got some of his first exposure to true, Brazilian Vale Tudo, as Rorion would often play VHS tapes of recent events in the Gracie Academy lobby. Craig would also get firsthand experience with Vale Tudo at the Academy, where he would occasionally fight challenge matches on the Gracies’ behalf.

At that time, Rickson was teaching at the Torrance academy and he and Craig had grown close and continue to maintain a strong relationship to this day. During these early days of the US Gracie Academy, Rickson promoted Craig to Brown Belt. It was around this time when Rickson also confided in Craig.

Craig needed to go to Brazil to continue his training, Rickson said. Rickson was becoming busier and had less time to train directly with Craig. Rickson felt the only way for Craig to find training partners that could push him would be for him to spend an extended period of time training at Gracie Humaitá.

Return to Brazil

Craig followed the advice. He had saved up enough money to last for six months of living expenses in Rio and towards the end of 1991 returned to Brazil. He got his own apartment in Rio, and he would either take the bus to Humaitá or, alternatively, Royler would drive him in his car for their daily training sessions.

While in Brazil, Royler asked Craig if he would like to compete in an upcoming Sport Jiu-Jitsu Gi tournament. Craig, still not feeling that Gi competitions were beneficial to Street Self-Defense training, declined. He did attend the event as a spectator but found the matches to be boring.

During this trip, Craig had also spent time with Helio. The two commiserating on the importance of Street Self-Defense training and bonding over their shared dislike of the Sport Jiu-Jitsu events that were emerging.

Prior to Craig’s time in Brazil expiring, Royler had a promotion ceremony at Humaitá. Royler promoted a few Brazilians to Black Belt and then dismissed the class. While the group was dispersing, Royler looked over to Craig and reacted as if he had just realized he had forgotten something. Royler jogged over to Craig and said that he had wanted to promote Craig to Black Belt, but as Craig was officially Rorion’s student, Craig would be promoted once he returned to California.

The Black Belt

In early 1992, upon returning to the Torrance academy, as per Royler’s prediction, Craig Kukuk was presented with his Black Belt by Rorion Gracie. The culmination of a little over ten years of five days a week dedication to Jiu-Jitsu had been realized and Craig became the first American and likely, the first non-Brazilian to ever receive a Black Belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. There was no ceremony. There was no ritual or celebration. Rorion merely handed Craig his new belt.

When Craig started training in 1981, he never thought about becoming an instructor. The career field did not exist in the United States (outside of the Gracies teaching in a garage). He was just happy to be learning what he felt was the most effective form of Self-Defense.

That changed once he was promoted to Black Belt, where Craig was given the opportunity to teach as well as train at the Torrance academy. At that time, Rickson was looking to leave Torrance and establish his own, independent academy. He approached Craig to come join him and teach at his soon to be created school. Craig declined saying that Rorion had already asked him via Royler when he was in Brazil if he would teach at Torrance when he returned. As Craig felt loyalty to Rorion as his primary instructor and because he only lived one block from the Torrance academy, Craig had previously accepted Rorion’s offer.

He began teaching at the academy around the clock. Monday through Friday, every week, Craig would teach private lessons from 8AM until noon and then again from 2PM into the late afternoon. Then he or Royce would teach the kids class, which would often contain Rorion’s children. Craig would then finish his workday at 8:30PM after teaching the adult group evening classes.

In early 1992, Rorion asked Craig to step into his office. There, Rorion shared with Craig that he intended to put on a no rules fighting event in the US to help promote Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. The event would be called “King of the Beach” and he asked Craig if he was interested in working on it with him.

Craig was supportive of the idea of bringing Vale Tudo to the American audience but felt that Rorion’s notion of having fights on a beach would be economically foolish as he would lose out on the ability to earn revenue through concessions, merchandising and pay-per-view rights. Craig thought the event could be presented similarly to how professional Boxing fight cards were produced. The two agreed to continue to develop the concept that just a year and a half later would become the first Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC).

Through his attempts to become a Hollywood actor, stuntman and fight choreographer, Rorion had developed a strong network of show-business contacts. He created a sizzle reel based upon Brazilian fight footage and leveraging those connections, Rorion and Craig would meet with various Hollywood producers and martial arts celebrities to garner interest in financing and promoting their proposed Vale Tudo event.

At their first meeting, an executive from a premium cable company became so disheartened with the violence he saw in the teaser trailer that he almost threw up. Craig and Rorion then realized they needed to tweak their promotional video and worked to create a second more tame version. Additional meetings with other executives were more productive and ultimately Rorion connected with Art Davies who would help him produce the first UFC.

It was shortly after his promotion to Black Belt where Craig approached Rorion about establishing his own Jiu-Jitsu academy. Up until this time, Craig had paid for all his own instruction, travel and associated costs. Now as a Black Belt, Craig hoped to strike out on his own and get the opportunity to earn a significant income. Additionally, Craig was planning to soon get married and had interest in moving to the East Coast of the United States.

He and Rorion agreed to financial terms, where Rorion would be compensated and Craig’s academy would, in turn, use the name Gracie Jiu-Jitsu and be considered the first franchised academy under Rorion.

However, in mid-1992, shortly before Craig was preparing to leave Torrance to open his foothold on the East Coast, Rorion approached him. According to Craig, Rorion said the previous terms they had agreed to, no longer worked for him and he wanted a new arrangement which would create a significant increase in Rorion’s ongoing compensation.

Craig felt this proposal was untenable and inappropriate as:

· They had already both agreed to a specific compensation structure

· Craig had been paying Rorion for over ten years of instruction at the Gracie Garage and the Torrance Gracie Academy

· Craig had been working at the Torrance Academy teaching classes mornings, afternoons and evenings for what he felt was very little compensation

The two men could not come to an agreement. Frustrated, Craig decided to stop teaching at Torrance all together. Shortly thereafter, Craig relocated to the East Coast. Fabio Santos would eventually take over Craig’s teaching responsibilities in Torrance.

Following Craig’s split from the Gracie Academy, he began receiving phone calls from martial arts publications, such as Karate Illustrated and Black Belt magazine. The journalists told Craig that he was not, in fact, a Black Belt in Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. Craig confirmed that he was and asked why they thought he wasn’t. The journalists claimed that Rorion was the one that told them. Craig responded by faxing the Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Newsletter to the journalists. In the document, produced and distributed by Rorion, it congratulated Craig on his promotion to Black Belt. After that, the magazines no longer challenged Craig’s claims.

The East Coast

Craig’s first academy opened in 1992 and was located in Red Bank, NJ. It was called Craig Kukuk’s Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. With the exception of Steve Maxwell’s Maxercise academy in Philadelphia, which opened in 1990, there was not really any other places to learn BJJ in the northeastern or mid-Atlantic US at the time.

Also, in addition to running his New Jersey-based academy, Craig travelled and conducted Jiu-Jitsu seminars for novices who did not have the opportunity to train in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu due to a lack of local academies. It was at one of these seminars in 1993 that Craig realized Rorion had moved forward with his King of the Beach idea without him. The other instructor at the seminar, Bill “Superfoot” Wallace, told Craig he had been recently hired by Rorion to commentate at the inaugural Ultimate Fighting Championship, to be held on Nov 3 of that year.

Partnership with Renzo

Although Craig’s academy was thriving, he knew there was still tremendous worldwide demand for instruction that could not be satisfied by his in-person classes and seminars. He felt videotape instructionals, still something relatively unheard of within BJJ at the time would be a successful product he could bring to market.

In mid-1993, he started by reaching out to Rickson to see if he would like to participate in the videos. The Gracie family champion was supportive but was ultimately non-committal. Craig then asked Rickson for Royler’s phone number. Royler was also supportive, but said he needed to talk to Rickson and Rorion first before agreeing to participate in filming. While Rickson encouraged Royler to film with Craig, supposedly Rorion and Helio convinced Royler not to do it as they felt it went against the family’s interests.

When Royler called Craig back to tell him he could not participate in the video shoot, Craig then asked Royler for Renzo’s number. Renzo was enthusiastic to participate and the two agreed to a compensation structure. Craig also agreed to fund the production and pay for Renzo’s travel expenses, so that the two could film the series.

The two completed filming and the “Renzo Gracie/Craig Kukuk BJJ” instructional series (also known as “Gracie Jiu-Jitsu A to Z” or “Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu from A to Z”) and it was released in Dec 1993, just one month after UFC 1, as an eleven volume VHS set.

The significance and timing of these instructionals cannot be overstated. While Rorion and Royce released a VHS series entitled Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Basics in 1991, they were the most introductory of techniques and there were only five volumes (later re-released as just three volumes). The information contained within the Gracie Academy tapes was the same day-one techniques that would be taught at a standard Rorion and Royce seminar at the time.

The Renzo/Kukuk tapes, released immediately after the first Ultimate Fighting Championship contains dozens of techniques and exposed buyers to moves, they would never get access to while training at the Torrance academy. The tapes were incredibly popular and still considered a landmark set of instructionals to this day due to their transparency, quality and quantity of information conveyed.

In early 1995, Craig received a call from Christopher Peters. He is the son of Hollywood film producer Jon Peters (Vision Quest, Caddyshack, Batman and the Color Purple, amongst others). Christopher was an avid martial artist and wanted to start a No Holds Barred event (it was not called Mixed Martial Arts yet) to rival the Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Craig was asked to compete in their inaugural Pay-Per-View event, which would be called the World Combat Championship. There would be a tournament format with grapplers (permitted to strike and submit) progressing through one bracket and strikers (permitted to only strike) progressing through a separate bracket. The two finalists would compete under the grapplers’ ruleset in the final match of the night.

Unfortunately, Craig was scheduled to have back surgery, but suggested Peters call his friend, Renzo Gracie. Renzo agreed to participate and ended up winning the tournament held on Oct 17 with three quick submissions.

As the demand remained tremendous and supply almost non-existent, Craig quickly expanded his real estate footprint. He:

· Moved from the Red Bank location into a Gold’s Gym in Middletown, NJ

· Opened a location in New York City on West 26thStreet between 6th and 7th Avenue

· Opened a location in the Bourse building in Philadelphia right across from the Liberty Bell and just two blocks away from Maxercise

Craig needed additional qualified instructors and leveraged his strong relationship with Renzo, to have him and Renzo’s student, Ricardo Almeida, join him in the US. The three would rotate almost daily between the schools to teach and oversee operations.

The Kukuk Death Squad?

It was there in New York that Craig would have a large, but little known impact on the art. At the time, Craig was very experienced and specialized in No-Gi, while much of Renzo’s experience and specialization had been just with the gi. As numerous MMA events were springing up and the Abu Dhabi Combat Club’s World Submission Wrestling Championships were being created, there was tremendous demand for advanced No-Gi training. Craig led these sessions at the NY academy, developing a generation of successful No-Gi and MMA grapplers and coaches including: Matt Serra, Rodrigo Gracie, Ricardo Almeida and John Danaher. While it is just speculation on the author’s part, but were Craig’s classes and style the origin of the Danaher Death Squad (DDS) system and their team’s future dominance?

His Own Vale Tudo Show and ADCC

During this period, Craig also came up with an idea to create his own US-based Vale Tudo promotion. It was to be financed by Sheik Tahnoun, the same man that would later create and fund the ADCC championships. Craig was able to connect with the Sheikh through Renzo via his friendship with Nelson Monteiro. Monteiro was the Sheikh’s original BJJ instructor when he was in California.

Rickson had committed to Craig to fight in the event and Craig was also in contact with Mark Coleman and Russian Olympic Wrestling Champion, Sanasar Oganisyan. Unfortunately, plans fell through and the event never occurred. It appears that the Sheik’s father, the President of the United Arab Emirates, did not want his family and country associated with Vale Tudo and told his son to stop the project. However, it seems the Sheikh, who was a dedicated Jiu-Jitsu enthusiast, still desired to pursue creating and hosting a Jiu-Jitsu related competition. Just a few months later, the Sheikh would announce the inaugural Abu Dhabi Combat Club World Submission Wrestling Championships. This was likely a compromise between the Sheikh’s desire to promote Jiu-Jitsu and his father’s dislike of MMA.

Through this period, Craig and Renzo continued to teach together, developing one of the best Jiu-Jitsu and MMA teams in the world. However, in late 1998, Renzo was looking to branch off and be on his own and Craig was concerned how he would continue to run three academies if Renzo left.

Idaho

While conducting a seminar in Fairfield, ID, Craig had a one-day layover in Boise until his flight back to New Jersey. As Craig still had access to the rental car, he spent the day driving around the surrounding suburbs. He was astounded by the beautiful houses and low cost of living in Idaho compared to New York and New Jersey.

Upon returning to the East Coast, Craig and his wife agreed to close the East Coast academies and move to Idaho. This occurred in early 1999. There, he would open a single academy, the Freestyle Training Center in Meridian. The academy would be No-Gi exclusively, sticking with Craig’s long held belief in the practical benefits of No-Gi for Street Self-Defense. While the academy was No-Gi, Craig did, however, continue to award traditional BJJ belts to his students. To date, Craig has awarded around half a dozen Black Belts directly.

By 2013, Craig was 52 years old, and his body was reeling from the effects of forty years of intense combat sports training. He and his wife chose to close the Idaho academy and relocate to Chandler, AZ. Craig and his family stayed there until 2020 when they decided to move back to Idaho where he resides to this day, retired from Jiu-Jitsu.

Product Development

While Craig no longer trains or teaches Jiu-Jitsu, he is still working within the world of Self-Defense.

It started back at his Middletown, NJ academy over twenty years ago. Craig was talking to one of his students who was a police officer about why he would bother training in Jiu-Jitsu even though he had so many pieces of lethal and non-lethal equipment on his police utility belt. The officer explained to Craig the difficulties of accessing his equipment during many real-world scenarios and that was why he needed Jiu-Jitsu.

That conversation stuck with Craig, and he has spent much of his time the last twenty years developing a tactical setup for law enforcement that will allow much easier access to equipment and allow police to leverage a variety of technological advances in communications and data sharing. Craig is now in the process of getting his patent approved.

Epilogue

After we finished addressing his biography, I wanted to engage Craig on some other philosophical topics:

Does he miss teaching? Does he miss rolling? As for Jiu-Jitsu, he feels at his age he just can’t do it anymore. Craig, does however, miss the interpersonal interactions. We talked at length about the camaraderie Jiu-Jitsu people share at academies; before and after class or just hanging out outside of the academy. He misses this aspect and still enjoys connecting with his former training partners and students.

Does he follow modern MMA? He said his sons will ask him to watch an MMA fight once every couple of years and he is happy to do that with them, but he does not actively follow the sport. He did praise Dana White and feels he has done a good job managing the company and is the right person for the job.

Does he follow Sport Jiu-Jitsu or No-Gi? Craig does not follow Gi but did recently watch some No-Gi. He listened to Gordon Ryan’s appearance on the Joe Rogan Experience and Craig became intrigued with checking out the modern state of competition. After watching some of Gordon’s matches, Craig felt that while people put their individual stamp on moves, things were not really new. He said that techniques appeared to be new to people who had no previous exposure to them. There was a cyclical nature to the popularity of the techniques. Interestingly, one of Craig’s only Black Belts, Jacen Flynn, had faced Gordon earlier at EBI6.

I asked Craig about his advice to BJJ students today. He said he did this because he loved it. He just wanted to train constantly. He acknowledged that this isn’t for everyone and recognized the training journey was a tough road. He said, “You just need to keep plowing and it takes a special kind of guy to do that.” Craig mentioned how people who think they are “tough guys” come into academies but can’t handle it and rapidly quit. “People just need to keep their head down and keep going and one day it will come together.”, he said.

We discussed his views on BJJ overall. He said that people often characterize him as a pure BJJ guy but that is incorrect. He was a boxer and wrestler who then learned Jiu-Jitsu. His philosophies and perspective stemmed from that. That is why he was always so obsessed with effective techniques and the practicality of No-Gi training.

Which accomplishment in Jiu-Jitsu was he most proud of? He said he was just proud to be part of Jiu-Jitsu and was glad that it was a component of his life. Craig originally viewed himself as a brawler and he felt Jiu-Jitsu humbled him. He also saw the positive impact on his students’ confidence and self-esteem as they gained skill in Jiu-Jitsu.

I raised the topic of Craig’s Coral Belt multiple times during our discussions. While academies and lineages use different “time in grade” criteria for 7th degree Black and Red Belt, the IBJJF sets the standard at 31 years. At the time of the interview in Dec 2022, Craig was only a few months from that milestone and would obviously be the first IBJJF recognized American Coral Belt. I asked Craig if that was something he was interested in pursuing or if it was something that he would like me to try and facilitate. Craig responded that he never had stripes on his Black Belt and never cared about promotions. There was no animosity or frustration in his voice. It was merely that this chapter of his life had closed, and he had moved on. When I pressed him once more about the belt, he humbly said that there is some guy out there (referring to the next American in line for the belt) and it would probably mean a lot to him to get the promotion, so let him get it and be the first one.

While I would like to see Craig be awarded the belt as I feel it would be the most correct action based upon the IBJJF regulations, I will respect his wish and drop the topic. His approach to the Coral belt is really a great representation of the man that I was fortunate enough to interview. Craig Kukuk cared about learning real and effective Self-Defense. He threw himself 100% into that effort and trained daily with best people in the world for decades. Craig did not care about ranks, sport tournaments or accolades. I am reminded of the quote from the 15-year-old boy that Craig had met in the garage decades ago who would later go on to win three Ultimate Fighting Championship titles. Royce Gracie said, “Your belt only covers 2 inches of your ass. You have to cover the rest.”. Craig Kukuk exemplifies this philosophy and it something that we should all attempt to emulate.

Craig Kukuk: America's first Black Belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

Craig Kukuk: The first American and possibly the first non-Brazilian to receive a Black Belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu

Those with dedication, commitment and belief in BJJ have fought great battles to ensure the future of Jiu-Jitsu and to spread our art. While many names known to us fought in the ring, the cage and on the streets for Jiu-Jitsu, others engaged in different battles. They combated the status quo, fought massive bureaucracies and provided much needed air cover to allow Jiu-Jitsu to grow and flourish within a variety of communities. BJJ’s adoption into the US Army training curriculum was no different.

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, from its inception, has been incorporated into military combatives training. It began with Sada Miyako, the first Japanese “Jiu-Jitsu” instructor to arrive in Brazil. When he arrived in Rio de Janeiro on December 16th, 1908, he was immediately contracted by the Brazilian Navy to teach their sailors unarmed combat. It is also possible that Miyako began teaching the Brazilian Navy even earlier. Miyako travelled from Japan to Brazil aboard the Brazilian Navy ship the Benjamin Constant, and it is believed he began holding classes aboard the ship for its sailors before ever arriving in Rio.

It is a model that Brazil repeated throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s, as we see Geo Omori and the Ono brothers often being contracted to teach hand to hand techniques to the Brazilian Army, Navy and Marines. This pattern repeated throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, via the Gracies, Takeo Yano, Luiz França, Oswaldo Fadda and many others. Eventually, critical mass was achieved with the Brazilian military internally maintaining a combatives curriculum and their own competent instructors.

I never served in the military, but as someone as part of the BJJ community for 25+ years now, I was somewhat familiar with its introduction to the US military in the 1990’s. When I started training, I had heard the SEALs in San Diego and Honolulu were training with the Gracies. Also, my instructor used to travel from our academy, meet up with Royce and the two would travel to train operators at Delta.

Years later, I heard the Rangers adopted a BJJ manual. It then spread as a standard training modality across the US military. I had even heard of a US Army General who had been awarded a Black Belt from Romero “Jacaré” Cavalcanti.

Little did I know that one day, I would meet that man and learn the story of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu’s adoption by the US Army.

I currently live in central Ohio and coincidentally it is also the home of the National Veterans Memorial and Museum.

I was teaching at Gracie Ohio one day and the owner and head instructor, Robin Geisler, came up to me and said, “Josh, General Ferriter might come in and take your class today.”.

Not knowing who that was, I guessed, “Is he the guy that got his Black Belt from Jacaré?”.

Robin responded, “That’s him. He is now the CEO of the Museum.”.

The General ended up not coming in that day, but I was intrigued to have someone so significant to the development of BJJ in the military so close by. It would be a couple years later that I would finally sit down and interview Lieutenant General Michael Ferriter, U.S Army (Retired).

Over the course of our discussion, we discussed his biography, his journey through BJJ and his philosophies on life and training. I have summarized our discussion below. I hope you enjoy.

Early Life Through Lieutenant (1956 – 1983)

Michael Ferriter comes from a military family. The son of an Army officer, he moved continuously as a child, relocating eighteen times during his first eighteen years of life. It was in the late 1960’s, while his father was stationed in Berlin, Germany, that a young Michael would begin down a path that would lead him to 35 years of distinguished service within the United States Army.

While in Berlin, Michael was interested in sports and got exposure to and interacted with enlisted personnel through various, on-base sports leagues. This time spent with enlisted infantrymen, inspired Michael to not only join the Army, but to serve in the infantry.

Michael enrolled in the Citadel military college in South Carolina in 1976. There, he would contemplate becoming a military lawyer, entering the Judge Advocate General Corps. However, two factors affected that decision. First, he was interested in tough Physical Training (PT) and was drawn to the infantry’s more intense culture and operational tempo. Second, while still an undergraduate, he attended the Army’s Airborne School, further enamoring him with the role and lifestyle of the infantryman and paratrooper. He would go on to graduate from the Citadel in 1979 and become an infantry officer. Up to this point, Michael would not yet have any experience with combatives training nor martial arts.

Captain Through Major (1983 – 1994)

As an Army Captain, Michael attended Ranger school, the Army’s premier small unit tactics and leadership course. While there, he was first exposed to military hand to hand training, often called combatives.

The combatives program at the time was quite rudimentary and only consisted of three 90-minute training sessions spread out over the course of the 60+ day school. The curriculum contained only very basic Judo throws and Boxing techniques; no sophisticated ground grappling or kicking. This was quite typical of the military at the time (the 1980’s), as there was no formally sanctioned combatives training and PT training was inconsistent across units. Soldiers, at the time, were not encouraged to continue to practice the combatives techniques, test them against each other nor evolve their skills. It was one time training and then soldiers were expected to move on and practice and develop other infantry skills.

As a Captain, Michael was assigned to the 75thRanger Regiment. While in the regiment he would hold a variety of roles and participate in Operation Restore Hope in Somalia.

Lieutenant Colonel Through Colonel (1994 – 2005)

As a Lieutenant Colonel, Michael would command 2nd Battalion 504th PIR of the 82 Airborne Division, before returning to the Ranger Regiment.

At that time, Michael had limited exposure to BJJ through watching the early UFC’s. In 1997, he got firsthand experience training via a seminar presented by Rorion and Royce Gracie. The Gracies were at 3rdBattalion, 75th Ranger Regiment conducting a two-week training course.

In 1998, Colonel Stanley McCrystal, as Commanding Officer of the 75th Ranger Regiment felt there were deficiencies amongst his Rangers. The unit’s charter, created by General Creighton Abrams in 1974 stated that the unit was to be "elite, light, and the most proficient infantry battalion in the world. A battalion that can do things with its hands and weapons better than anyone. Wherever the battalion goes, it must be apparent that it is the best." With this in mind, McCrystal sent a handful of Non-Commissioned Officers to Torrance, California to train at the Gracie Academy. The idea was for these NCO’s to participate in a “train the trainer” program so that they could return to the Ranger Regiment to create a course, lead and train others in combatives.

Also, during this time, Michael attended the Fletcher school of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts completing a Senior National Defense Fellowship.

While a Colonel and Brigade Commander of the Infantry School Brigade (11th Infantry Regiment), Michael was summoned to his four-star General’s office and ordered to rewrite the Army infantry officers’ training manual to “toughen up” their Lieutenants. The goal was to increase the young officers’ proficiency in rifle and pistol marksmanship as well as hand to hand combat. The goal was to create a more capable, combat effective and resilient group of leaders by “scuffing them up”.

Michael took an inventory of Army capabilities at the time and realized that the General was correct. Of the sixteen Army branches at the time, only nine were fully qualified at basic rifle marksmanship. Similarly, only nine of the branches required their soldiers to sleep in the field as part of training.

Michael set to work establishing new standards. He required all Army officers to perform fieldcraft, obtain proficiency in first aid, ruck with a 45-pound rucksack and qualify with both rifle and pistol.

In addition to those skills, Michael could also see the value in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu training. How the art could develop his officers’ confidence, ruggedness and self-awareness. He felt he had an opportunity to provide people with a skill that would make a difference in their lives.

The issue was that there was no official Army combatives program and the military was very hesitant to allow training without bureaucratic approval. Matt Larsen and Troy Thomas, two of the Ranger NCO’s that had been part of the contingent that had originally trained at Torrance, approached Michael about formalizing and documenting an official combatives program. The program would utilize Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu as a base and add in key elements of Wrestling, Judo, Boxing, Muay Thai and Kali.

Michael thought it was a great idea, but many senior officers were against the approach. It was just too new, too different and there was no established roadmap. As opposed to the traditional military method of teaching a handful of basic hand to hand techniques to new recruits, this approach would teach the soldiers and officers a framework for training and incentivize continual learning and skill development.

In the legacy system, once rudimentary training was completed, Army personnel did not really get to continue to practice those skills or learn new ones. There was no incentive or avenue for them to do it. There were no formal instructors, no progressive training, no facilities and no competitions. Michael and the Ranger NCO’s sought to change that. They knew it would be an uphill battle.

They encountered roadblocks at every step of the way, yet the team continued to drive forward. They embodied the Rangers’ iconic motto, “Rangers, lead the way!”. At first there was no course manual, so they wrote one. Then their issue was that the manual was not approved by Command, so they then got it approved. Then there was no dedicated facility, so Michael sought one out.

He identified a building at Fort Benning that was being used as a book warehouse for training manuals. Michael then reached out to the base commander and asked if there was a possibility of a trade. The two agreed and the books were removed from the warehouse. The building would then be converted into the Modern Army Combatives Training Center, AKA the “Thunderdome”.

At first there were no certified instructors in the newly created Army Combatives program, so the team established four levels of instructor training to create leaders who could organize and supervise combatives training at the platoon, company, battalion and brigade levels.

Fort Benning is in Georgia and only a two-hour drive from Romero “Jacaré” Cavalcanti’s home base. Jacaré is one of only a handful of people to have been promoted to Black Belt by Rolls Gracie and is currently an 8th degree Red and White Belt. He was famous in Brazil for starting the Alliance team and producing champions such as Fabio Gurgel, Rodrigo “Comprido” Medeiros, Roberto Traven and Leo Vieira. In 1995, Jacaré would move to the United States, first to Florida and then to Georgia to establish his headquarters academy.

The senior personnel from the combatives school, including Larsen and Ferriter, began making the drive to train at Jacaré’s academy. Jacaré further developed them as practitioners and teachers and assisted them with demonstrations for visiting VIP’s from the Department of Defense.

Flag Officer (2005 – 2014)

In March 2005, Michael was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. While his responsibilities increased, he continued to train and kept his finger on the pulse of the Combatives program. After eight years of training, he was awarded his Blue Belt directly from Royce Gracie.

To continue to develop and promote the combatives program, in 2009 Michael formed an advisory council of other service members, veterans, BJJ trainers and Self Defense experts. The group included Greg Thompson, Frank Cucci, Bill Odom, Tony Blauer, Jacaré Cavalcanti, and both Rorion and Rener Gracie. The panel would stay connected and continue to develop, steer and unify the Army’s training program.

At that time, Michael was deputy commanding general of the XVIII Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg. Due to the ongoing Global War on Terrorism, he felt there needed to be more emphasis on training for Close Quarters Battle (CQB). He had more techniques and training related to stand up, controlling distance, weapon retention and takedowns added to the curriculum. Matt Larsen pushed for more competitions to be integrated into the program. The idea being that competition would incentivize soldiers to train, improve and add to their skillsets. It was also at this time in 2009, while at Fort Benning, that Michael was promoted to Purple Belt by Rigan Machado, “Papa” John Gorman and Matt Larsen.

During his second and third deployments to Iraq, the General continued to exert his influence to expand and integrate the program in the Army’s DNA. He was commanding general of the Army’s Installation Management Command, responsible for the operation of all Army bases worldwide. He was able to leverage his position to have grappling mats delivered to Forward Operating Bases and Combat Outposts, providing spaces for soldiers to train, compete and realize the benefits of mat time, even while deployed to combat zones. He even flew Ryron Grace and Gui Valente to Iraq to have them conduct seminars for the troops. The General also had bases around the world dedicate spaces within exercise facilities for mats so soldiers could train. It was at this time in 2012, that the General was promoted to Brown Belt by Jacaré.

I asked the General about fear of injuries related to pushing for BJJ training while deployed and if the military had reservations about risking the operational capabilities of their troops. The General replied that he saw many more injuries over the years from soldiers playing racquetball and basketball than from training and competing in BJJ and combatives.

The program continued to grow over time, becoming firmly entrenched within the culture of the Army. Privates who started training in the program back at its inception were now Sergeants Major and work to ensure the continued integrity and standards of the program.

In March of 2014, after seventeen years in Jiu-Jitsu, Lieutenant General Ferriter was promoted to the rank of Black Belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu by Jacaré Cavalcanti, becoming the first US flag rank officer to do so. Three months later, after 35 years of continuous service to the country, the General retired from Active Duty in the US Army.

Among his many accomplishments, the General is often referred to as the “Godfather of US Army Combatives” and I feel it is definitely an apt title.

Post Military Career (2014 – Present)

Upon retiring from the Army, Michael continues to serve his community. He founded The Ferriter Group and the Hands On Inspired Leadership (HOIL) program to provide leadership and life training to executives, veterans, service members’ families and high school groups. He leverages his lessons learned through his extensive military service and time in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu to teach people how to overcome obstacles and achieve their goals.

Additionally, in 2014, the General helped establish the Veteran Golfers Association, where he continues to serve on their board of advisors. The program was designed to provide a positive and supportive environment to veterans and currently has over 14K members. The program has had a positive impact on veterans’ mental health, with zero members of the association committing suicide since its inception.

In 2015, the General partnered with the Black Rifle Coffee company to create the U.S. Veterans Business Alliance, an organization to assist veterans establish, maintain and grow their businesses.

In 2018, the General was asked to serve as the President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Veterans Memorial and Museum. The Museum located in Columbus, OH honors the veterans of all branches of service, from both peacetime and wartime.

As CEO, the General’s goal is to honor all veterans from all time periods. His vision is not simply to honor the past, but to bring opportunities to the veteran community and their families. These opportunities apply not only to employment, but to health as well.

The General continues to believe in the transformational power of Jiu-Jitsu, both from a resiliency building perspective and as a tool to heal physical and emotional trauma. As such, he created the National Veterans Memorial Jiu-Jitsu program. A BJJ academy that is run directly out of the museum at no cost to students. The program is open to everyone: veterans, their families and civilians alike. The school offers instruction every day of the week.

Overall, it was great to converse with the General, to hear his story firsthand and to pull back the curtain on what it took to transform the Army hand to hand program, improving the efficiency, effectiveness, resiliency and health of the troops.

If you are ever in Columbus, I suggest you stop by the museum to take a tour and then put on your gi and hop on the mat.

Visit www.NationalVMM.org to learn more.

Lieutenant General Michael Ferriter, U.S Army (Retired). BJJ Black Belt.

Lt. General Michael Ferriter, US Army (Retired) on the mat.

I usually begin these articles with my personal views as to why I selected the interviewee and why I think they are important to the history of Jiu-Jitsu. In this case, it is a slightly different scenario. While Tony has indeed been an important part of the history of Jiu-Jitsu and the development of its culture, unlike the other interviewees, I have known Tony since the first day that I stepped on the mat almost thirty years ago.

While Tony and I have not really been in contact the last twenty or so years, once we started talking again via Zoom for this article, it was like we hadn’t skipped a beat. Over the course of multiple sessions and several hours, I was able to put together Tony’s story and its intersections with the history of Jiu-Jitsu.

In thinking about how to summarize Tony and why I wanted to write this article about him, I thought about our similarities and our differences. We were about the same age, the same size, both profoundly affected by Royce’s success in the early UFCs and both of came up together side by side in the spartan crucible that was Maxercise in the 1990’s.

But it was the differences between us that fascinated me. We started at a time when there were almost no instructional videos. Rorion had put out the Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Basics series, but that was about it. There was no Pan Ams, there wasn’t even a World Championship or an IBJJF. There was no Grappler’s Quest. No NAGA. No ADCC. There weren’t even many academies. Maybe a dozen in the entire world outside of Brazil? The internet was still in its infancy and there was no easy way to get information on what was going on in other academies in the US or Brazil.

It was as if both of us, as teenagers, stood together on a precipice, looking into the void of the unknown. No one had any idea what Jiu-Jitsu would become or where we would fit in. There just was no roadmap of what a career in Jiu-Jitsu was or how to get one. I took the safe route. I prioritized getting my degree and a full-time job. I focused on getting married and starting a family. I wanted to keep doing Jiu-Jitsu, but I was not willing to take the risk and upend my life to do it. We did not have a term for it at the time, but I would become what would eventually be known as a hobbyist.

Tony looked into that same void. He saw the things I was pursuing. He saw the risk, the instability and the uncertainty ahead if he followed a different path. Unlike me, those things did not dissuade him, and he stepped into the void, not sure where that decision would take him.

Early life

Tony was born in 1978 and grew up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He has one sibling, a sister who is six years older than he is. She was always involved in sports, and as Tony grew up, he too followed in her footsteps.

His parents put him into soccer, baseball and football. While Tony was a little smaller than his peers, he was always a good athlete and excelled at baseball. It was the 1980’s, and unlike today, kids spent significant time each day playing outdoors. Tony spent much of this time as a child riding his bike around the neighborhood.

He continued playing sports throughout elementary school and into middle school where he played on several travel teams. Tony racked up a decent amount of injuries during this time, even breaking his arm while playing middle school football.

During his youth, Tony also spent a decent amount of his time watching VHS movie rentals. He loved the martial arts section in the video store and was enamored by Bruce Lee and ninja movies. He was also a big fan of Pro-Wrestling at the time.

It was exposure to these movies that got Tony interested in learning martial arts. He wanted to learn Kung Fu and Judo, however in 1993, when he was 14, his parents enrolled him in a local Tae Kwon Do program. Due to his interest in martial arts, in addition to the lessons, his parents also bought Tony a subscription to Inside Kung Fu magazine.

While reading the magazine one day, Tony saw an advertisement presenting Royce Gracie’s recent success at the first Ultimate Fighting Championship event. The ad offered a VHS instructional series entitled Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Basics and was available for sale via mail order from the Gracie Academy in Torrance, California. Tony called the phone number and placed the order.

By purchasing the tapes, Tony was now unknowingly put on the Gracie Academy customer mailing list and soon received a letter informing him of an upcoming Gracie Jiu-Jitsu seminar that would be held nearby his home in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The instructor would be Relson Gracie and if Tony was interested, he was to call the local organizer, Steve Maxwell.

While Tony ended up not attending the seminar, he received the videotapes and began diligently practicing the techniques in his living room with his friends.

Shortly thereafter, UFC 2 occurred and Royce once again was crowned champion. Following UFC 2, Tony had his first challenge match with a neighborhood boy who had heard Tony was learning Jiu-Jitsu. Tony took the kid down, mounted and won via choke. He used the same moves he had been practicing from the videotapes. The victory caused Tony to fall in love with Jiu-Jitsu and brought him notoriety from kids in the neighborhood and at his school.

However, some people were telling Tony that Gracie Jiu-Jitsu and ground fighting were just fads and would quickly fade from the limelight. Tony felt differently. He believed this was a brand-new perspective on the realities of fighting and soon the rest of the martial arts community would come around to acknowledge that. This was something big. It was just the beginning and he wanted more.

Maxercise

Tony was now 15 and got his driver’s license. Steve Maxwell’s academy, Maxercise, was one of the only BJJ schools anywhere in the US at that time. It just so happened to be in Philadelphia, less than an hour away from Tony’s house. He wanted to get in his car and drive down to join the school, but Tony’s mother did not want the novice driver to make the trip. Instead, she insisted that he take the train to go check out the school.

They negotiated back and forth and ultimately, Tony’s mother agreed to drive him down to the academy for his first class. It was May 1995. UFC 5 had just happened the month prior with Royce drawing with Ken Shamrock in the Super Fight main event.

As luck would have it, Tony would not get a chance to train that day. There was a fire next door to the academy and the students were not able to get on the mat. Instead, Steve, who was a Purple Belt at the time, hosted a VHS viewing of UFC 1 in the Maxercise lobby. Tony was hooked and began training shortly thereafter.

A month later, it would be the summer after his sophomore year in high school and Tony would venture to the city to train every day. As was the tradition, the summer classes would all be No-Gi, consisting of Gi pants and a T-shirt. Tony would spend his days training under Steve and the assistant instructor, Phil Migliarese.

During his early days at Maxercise, Tony was able to witness firsthand “Gracie Challenge” matches where Phil, as a Blue Belt, was defeating bigger and stronger people with ease. It further cemented in his mind the effectiveness of BJJ.

As autumn came, Tony began his junior year of high school and classes at Maxercise returned to the Gi. At the time, Tony disliked changing back to Gi training as he felt the pace of No-Gi rolling was faster. He also felt disadvantaged due to his limited experience in defending collar chokes. Tony committed himself to improving in the Gi.

It was at this time that an eighteen-year-old Josh Simon would join Maxercise, but that story is detailed elsewhere on this site. It was also around this time that Tony, due to his young age and slight frame of around 130 pounds received the nickname “little Tony”.

At that time, Tony was exposed to the traditional Jiu-Jitsu curriculum. Sport Jiu-Jitsu competitions, while beginning to get more popular in Brazil were still in their infancy. Most Jiu-Jitsu training was focused on Self-Defense applications. Taparia, the method of training where slaps are used to simulate striking was commonly employed to ensure students were prepared for the realities of the street.

The Gracie Challenge matches were still quite common, with people walking in off the street and demanding to fight in order to prove which style was best. While many of the fights that happened at Torrance had the Gracies as the fighters, at Maxercise, we just had us.

It was common when people came into challenge, that they would face Steve or Phil, but many times, the instructors would select Blue Belts or even White Belts to take on these street fighters. Tony witnessed many of these fights and it further convinced him of the effectiveness of Jiu-Jitsu in real world Self-Defense scenarios.

In addition to developing his Jiu-Jitsu at Maxercise, Tony matured in other ways as well. While he was only a high schooler, while at the academy, he would spend his days with college kids and professionals. It exposed Tony to a variety of new viewpoints and to people with different life experiences. At the time, Maxercise (and most of the country for that matter) only had a handful of Blue Belts. Maybe three or four besides Phil. Tony really credits these senior students with his development as they had patience and were kind to him.

On weekends, as he was not at the academy, Tony would take his newfound skills and have challenge matches against the kids from his town. He would keep a notebook with descriptions of each match. His friends started videotaping the fights.

I remember Tony bringing in the videotapes and showing them to us on the TV at Maxercise. We jokingly nicknamed him the “King of the Suburbs”. A reference to Marco Ruas, who had just won UFC 7 and was known as the “King of the Streets”.

Tony, and all of us at the academy, thought it was completely normal for a minor to take other teens into the woods every weekend, beat them up, videotape it and document it in a notebook. That was just the environment we came up in. Proving the efficacy of Jiu-Jitsu to the masses was our mission. Often, the only way to prove it to people was to fight them and beat them. It made sense to us. It was what the Gracies did, so, it was what we did. Perhaps now, looking back at these things thirty years later, they may seem a little weird when filtered through the lens of current culture.

People outside Maxercise often did not believe that Tony was actually training at a real Gracie affiliate or that he was learning real Gracie Jiu-Jitsu. It was only when he would show people pictures of his fights and training or wear his Relson Gracie T-shirt, that people believed him.

During that junior year of high school, Tony challenged his school’s entire wrestling team to fight. The coach heard about it and said to Tony, “You want to do what!?!?” and immediately prohibited the fights from happening.

At that point at Maxercise, beginner students were given large, yellow paper cards with their names on them. We would take them to class and the instructors would mark them as we took each lesson. Tony really liked that system and took pride as his sheet filled up. He wishes that he still had the card now as a symbol of his early commitment.

As the time passed from 1995 into 1996, Jiu-Jitsu representatives kept winning PPV events and the class sizes at Maxercise grew.

In the summer of 1996, after Tony’s junior year completed, he ended up going on his first ever plane trip. It was to Torrance, California to visit the Gracie Academy. He went with Phil and trained there for a week.

While there, they stayed with one of the prominent students at the Gracie Academy, Jon Burke. Tony was able to get a feel for the California/BJJ lifestyle and he liked it. Royce taught the classes and Tony saw how much Steve and Phil were respected by all of the people at the Torrance academy. The trip was eye opening for Tony and he started working out a plan to move to California and dedicate himself to Jiu-Jitsu.

The summer of 1996 also saw Tony competing for the first time. Maxercise would have an annual tournament every summer. Relson was the referee and it was in the Gi. While it was mostly Maxercise people who participated, we did have outsiders show up to compete as well. Tony, still a White Belt, lost via a punch choke while Tony had his opponent in his guard. Tony frustrated with losing, later approached Relson to learn how to defend it in the future.

As Tony entered his senior year of high school, he came up with a plan that would allow him more time to develop his Jiu-Jitsu skills. He would create a “work study program” where he would receive high school credit, for working at Maxercise. The extra time at the academy would allow Tony more opportunities to train.

Tony’s father was not against the idea and knew this was his son’s passion. His guidance counselor signed off on it, but Tony’s mom was not so sure. She wanted her son to graduate high school but could not see a professional future for Tony as a BJJ competitor (the concept did not really exist back then). She encouraged Tony to think bigger and either figure out how this could be a real profession or attend college.

Tony would go to school and take English, philosophy and gym class. He then would head off to Maxercise for the rest of the day. At this point, Tony was just doing menial tasks, cleaning and running errands to help the Maxwells and the academy. Eventually, Tony would be used as the uke for the women’s Self-Defense program taught at Maxercise known as RapeSafe. The curriculum, created by Rorion, was one of the first of its kind in terms of creating a formal teaching structure and lesson plans and having satellite schools teach it.

Tony used the funds he was making at Maxercise to begin to save up for his move to California.

He continued to see Maxercise and BJJ grow. Monthly dues remained at $50 a month, but unlimited training was replaced with a limit of sixteen lessons per month to keep classes from overflowing with students.

In the fall of 1996, Tony took his first trip to Hawaii. The purpose of this trip was to train with Relson at his academy there and compete in Relson’s Hawaii Open tournament. This trip is where Tony was first exposed to and became enamored with surf culture.

Tony, who was one stripe Blue Belt at the time, won all three matches to capture Gold in his weight class. Unfortunately, right after the tournament, Tony popped his knee and had to spend the remaining days of his trip stuck in bed.

Upon returning to Maxercise, Tony quit his part-time busboy job and began working full-time at the academy. With his now full-time commitment to Jiu-Jitsu, Tony promised himself he would eventually move to California and enroll in the Gracie Academy’s Instructor Certification Program. Tony began saving his money and focused on graduating from high school.

The Instructor Certification Program is a complex piece of BJJ history and it is important I set the stage properly for those who are not of that era. In the mid 1990’s there were only a handful of academies in the US and they were run by established and famous Black Belts like the Gracies and the Machados. Demand for Jiu-Jitsu instruction was at an extreme level, with PPV event after event documenting Jiu-Jitsu fighters easily defeating fighters from every other style imaginable. Rorion realized, even with the Gracie Academy classes and VHS instructional tapes, he could not satisfy all the demand, so he created the instructor program to teach people Jiu-Jitsu and how to teach Jiu-Jitsu. The idea was that the students would eventually become certified in Jiu-Jitsu and then open satellite academies affiliated under the Gracie Academy.

It was a way for Rorion to control the quality of instruction and the curriculum and to create additional revenue streams. One from the tuition from the instructor candidates and one from the affiliate fees the satellite schools would pay in perpetuity.

Maxercise, with Steve as a Purple Belt, and Gracie Ohio, with Jeff Hudson as a Blue Belt, were examples of the affiliate schools at the time, known as Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Training Associations (GJJTA). Even though Steve and Jeff were not yet certified instructors, they were both enrolled in the program.

It may seem strange to today’s practitioners that people would need to be formally certified by someone to teach or open up their own school. Nowadays, people just do it without anyone’s blessing. But then, we really did not know anything else. Rorion set the standards and we followed. It is kind of like if you want to become a medical doctor, you know you need to first attend medical school. There is no other way to become an MD. We were all convinced at the time, if you were going to teach Jiu-Jitsu that you needed to be certified to do it by Rorion.

Enrollees were required to be Blue Belts and the program had two tracks. One was part-time where people would fly to Torrance, take classes for a couple days or weeks at a time and then fly back home. This was the most common track as many people had full-time jobs and families and could only dedicate time sporadically to becoming certified.

The other track was for full-time students. They would give up everything, move to California and work and train at the Gracie Academy full-time in an attempt to accelerate the learning and certification processes as much as possible.

The tuition was $300 a month for part-time students and $600 a month for full-time students. In addition to the tuition, full-time students were required to work forty hours per week at the Gracie Academy for no pay and could not hold a job that interfered with their Academy working hours. Work at the academy included janitorial, administrative and teaching assistant/uke responsibilities. The real kicker was that there was no set curriculum, no set program duration and it was not clear how close you were to graduating.

Can you imagine? You uproot your life, pay Rorion $600 a month, work for him forty hours a week for free doing whatever he wants, and you may get certified to teach Jiu-Jitsu at some point down the road. Would it take one year? Would it take twenty years? No idea. There was not even a guarantee that you would ever get certified.

Going back to the medical school analogy, it has a set duration, class list, required GPA and total tuition cost. You could fail out, but at least you knew how long it should take, what it should cost and what was expected of you.

None of that existed for the Instructor Certification Program. It was a setup that I always took issue with. It was not a scam per se. But I always felt Rorion took too much and gave too little. But that was what happened in the 1990’s with the extreme disparity between supply and demand. Rorion could operate under any rules he wanted, and people were happy to comply. Steve, Jeff and Phil were part-time students. Tony wanted to be full-time.

Tony attended a seminar that year with Royce in Connecticut. There, they discussed Tony’s interest in the instructor program and his concern about not having enough money saved up to be able to support himself and pay tuition. Royce convinced him not to worry about saving up too much money and urged him to join the academy’s program as soon as possible.

Upon arriving home from the seminar, Tony told his parents he was moving and bought himself a one-way plane ticket to California.

The Gracie Academy

Tony arrived in Torrance in early 1998. He was just nineteen years old, had $1,000 in his pocket and no real plan on how to get set up in his new life. He spent his first night in California at the Driftwood Motel, before befriending the owner who offered him a room to rent in their house in Redondo. In exchange for $300 a month and helping teach the homeowners’ son English, Tony had a long-term place to stay.

He then walked to the local Goodwill and bought a broken bicycle for $5 and fixed it up so that he could pedal the five miles each way to the Gracie Academy.

Tony had two weeks until his enrollment began, and his $1,000 savings quickly dwindled to just twenty-five cents. Fortunately, he got a minimum wage job as a busboy in a nearby Mexican restaurant and was able to start saving up money.

At the academy, he started as part of a full-time cohort with around eight other Americans and one Brazilian. Tony was the youngest of the group. As he got to know the other instructor candidates, Tony was impressed with their dedication as some had sold their homes and most of their possessions to be able to afford participating in the full-time program.

In addition to their labor around the academy and taking regular Jiu-Jitsu classes as students, Rorion would teach them a special class once a month on how to teach Jiu-Jitsu.

Rorion’s standards were high, and he expected each technique to be taught a specific way. He would call out members of the cohort and have them teach a technique to Rorion and the rest of the trainees. Rorion would then critique the student’s performance.

In time, Tony was asked to be the bad guy for RapeSafe with Rorion as the instructor. This led to Tony gaining additional time interacting with Rorion. Tony would eventually begin teaching yoga at the Gracie Academy on Friday nights. In consideration of this, his monthly tuition fee was reduced.

A typical day for Tony involved him riding his bike to the academy before the 9am start of classes. He would wash rental Gi’s, clean the bathrooms and fold towels. He would then serve as an assistant instructor in adult classes, teach kids class and roll every chance he could. The academy was closed on Sundays and the trainees would take the day off.

The academy, at the time, offered a handful of class formats:

- Basics: Often taught by Americans who had already completed the Instructor’s program, such as Jon Burke, Eric Maier, Marc Baumiester and John Crouch. Trainees would participate as assistant instructors.

- Advanced: Taught by Royce or Helio Black Belt Carlos “Caique” Ellias.

- Kids: Taught by people in the instructor certification program.

- Privates: The trainees served as the uke, but never received payment for this additional duty. Sometimes senior trainees would teach privates and be monitored via video by Rorion who would later critique them.

The members of the cohort would participate in periodic, formal performance reviews with Rorion and Sam Rand, the academy’s business manager. The trainees would be measured against each other as well as Rorion’s ideals.

Tony received the highest rating amongst his peers but was told that he was too introverted and needed to work on that. He was still just 19 years old but learned important lessons while at the academy about not procrastinating and taking feedback from others to improve.

While at Torrance, Tony had some exposure to Helio when he would visit. Their interactions were minimal as Tony did not speak Portuguese and Helio did not speak English, but Tony remembers being chastised by Helio for folding towels with incorrect technique.

At this time, Rorion wanted to create a national Jiu-Jitsu tournament, but under his own set of rules. The first-ever Gracie Jiu-Jitsu National Championship would be held in 1997 and be open to the Gracie Academy, Relson’s academy and all the Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Training Association affiliates. Rorion’s major modification to the ruleset was that all the matches would be “No Time Limit”.

The way it would work was that the matches would continue until there was a submission or someone scored 15 points. Rorion was attempting to disincentivize stalling, but it obviously caused problems to run a tournament in this manner. I competed in the 1997 tournament, and it was nuts to have one match last a minute and then have all the people in your weight class have to wait an hour for a match to finish in order to progress the bracket.

At the end of 1998, another significant event occurred. Royce competed in a no time limit, no points Sport Jiu-Jitsu match against Wallid Ismail in Rio de Janeiro. Tony and many of the other instructor trainees were called upon to help Royce prepare. Tony found it odd that for his match against an elite Black Belt, Royce would be spending his time training with just Blue Belts.

Royce would ultimately lose the match via clock choke. Tony was home in Pennsylvania at that time spending Christmas with his family. Tony knew the match occurred and called Torrance to find out the results. Upon hearing of Royce’s loss, Tony felt that he needed to compete against other academies to avenge the loss.

Tony entered the Copa Pacifica, winning his first two matches before losing to a student from Rickson’s via sweep. Rorion became very against Gracie Academy students competing against other academies. He was ok if people won, but did not want to take the risk of a single loss, regardless of the scenario.

It was at this point that Tony started to see the darker side of the business and understood some of other people’s criticism of Rorion and how he conducted himself. He also started to see other people leave the instructor’s program or the Gracie Academy affiliation entirely. The exodus would eventually include Steve, Phil, Caique and even Royce.

Tony continued to compete during this time period, both in the in-house tournaments and the national championships. One year, he won the in-house weight class, open weight and then won his weight class at the nationals. At the nationals that year, Rorion split the Open bracket into two divisions with Tony winning the Open up to 175 pounds category.

Sometimes there would be an additional, informal in-house tournament at the Gracie Academy. It would be held in an ongoing, progressive basis throughout the year. Students would be at the academy and Rorion would announce you were now having a match to progress your bracket, right then and right there. It ensured people could handle the stresses of fighting and were always prepared to compete.

Tony spent almost two years in Torrance working, training and teaching at the Gracie Academy. He felt it was a valuable experience. Tony learned a systematic approach to teaching and got to train daily with some of the top people available in the US at the time.

While Tony was one of the people to stay in the Instructor Certification Program the longest, he did not achieve certification before he left as a four stripe Blue Belt. While other people were leaving, Tony planned to stay loyal and remain in the program. However, he says that Rorion, upon seeing others leave, became suspicious of Tony and accused him of wanting to leave and abandon the affiliation. Tony informed Rorion that it was time for him to start college and that he would return to the program during the summer breaks. With that, Rorion gave Tony his blessing to leave and return to Philadelphia.

When asked if he felt he was taken advantage of by the program’s structure, cost and lack of transparency, Tony said he did not. He felt the training was similar to the military where he learned to be selfless, lose his individuality and to act in a professional manner. The Gracie Academy at the time was duplicating much of the culture and etiquette of the 1950’s Gracie Academy on Rio Branco Avenue in Rio de Janeiro and Tony still feels that was a noble approach to creating Jiu-Jitsu instructors.

Back to Philadelphia

It was 1999 when Tony left the Gracie Academy and returned home to Pennsylvania. He enrolled in local community college, eventually transferring to West Chest University with a goal of completing a BA in Elementary Education.

Upon returning to Maxercise, Tony could see the changes underway. Maxercise had recently severed ties with Torrance and changed affiliation to Relson. There was bad blood on all sides and when Royce came to the East Coast to conduct a seminar, Tony was required to ask Steve’s wife for permission to attend. When Tony attended the seminar, he could see the changes in Royce as well. Tony got a feeling that Royce would soon leave the Gracie Academy, which came to fruition shortly thereafter.

Tony continued to train at Maxercise. He now taught the kids’ classes, beginner class and women’s Self-Defense. He also continued to compete, winning the in-house tournament at his weight class and the open weight at Blue Belt and then Tony took his first trip to Brazil.

A small team from Maxercise would travel to Rio to compete at the World Jiu-Jitsu Championships. At this point, Carlos Gracie jr. was so interested in attracting international competitors to Brazil to participate in the tournament, that there was no pre-requisite or qualifier for non-Brazilians.

Tony lost his first match when his opponent stalled from top half guard. At that point, Tony realized the limitations of the “Helio” relaxation/Self-Defense approach and saw how it was not the best strategy for time limit Sport Jiu-Jitsu matches with points, advantages and stalling.

While at the tournament, Tony was able to see Saulo Ribeiro compete and was impressed with his ability to be a Gracie Humaitá student, but also push the pace of matches and dominate the competition.